The internet is so much about what to look at.

For me, that’s weird. You see the bulk of the first part of my life was bound up with reading—which is all about looking at things, reading words, but has little to do with seeing, with reading pictures.

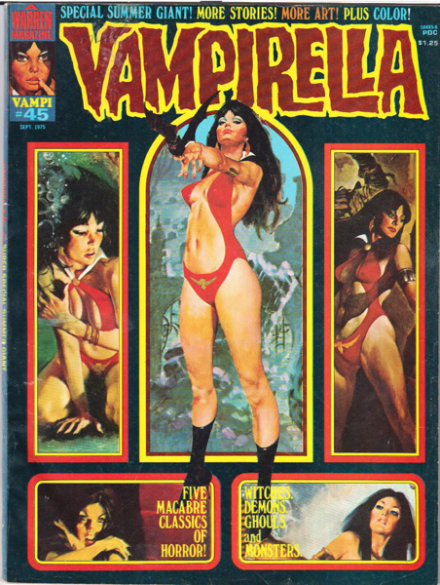

It is true that as a kid, I was all about reading while seeing, with Richie Rich, Mad Magazine, Vampirella, Batman, Eerie, and Plop! infecting the technicolor corridors of my imagination.

But after that came college and graduate school with a major in literature—so novels took over (that and critical theory), so words came to dominate the scene of my life.

And so, now, I return to pictures.

“The Medium is the Message,” Marshall McLuhan told us, and he was right especially when you think about old pictures and Polaroids from the 60s onward. Now decaying and disappearing, Polaroids are so much an image of yesterday for my generation (I was born in 1961), that we find ourselves magically drawn to the form today (even if it is just in the form of Instagram filters, digital magic that transforms a picture from 2016 into the semiotic twin of a picture taken in 1966).

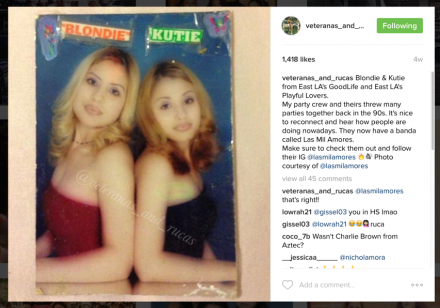

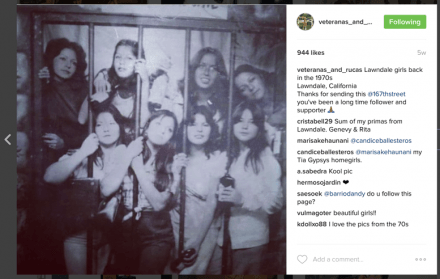

Which brings me to the current rage for Guadalupe Rosales’s collective curating project on Instagram called Veteranas y Rucas: SoCal Youth Foto Archive, recently profiled in L.A. Weekly, Remezcla, and Mitu.

I keep going back time and again to see a past that mirrors much of mine—though tons of the pictures capture life in Southern California before 1990, they evoke an aesthetic, a feel, a groove, a rhythm, and an eros, more on that below in the last picture, that I can’t get enough of.

Some folks get addicted to opioids, I am done in by a lowrider car from 1973. Some like the sweet euphorics of Mollies (Ecstasy), I get sidetracked by the raging hair on some random “ruca” or “veterana” that takes me back to Laredo, Texas, circa 1977.

Here are some recent snapshots from the site that I bookmarked that are talking back to me…

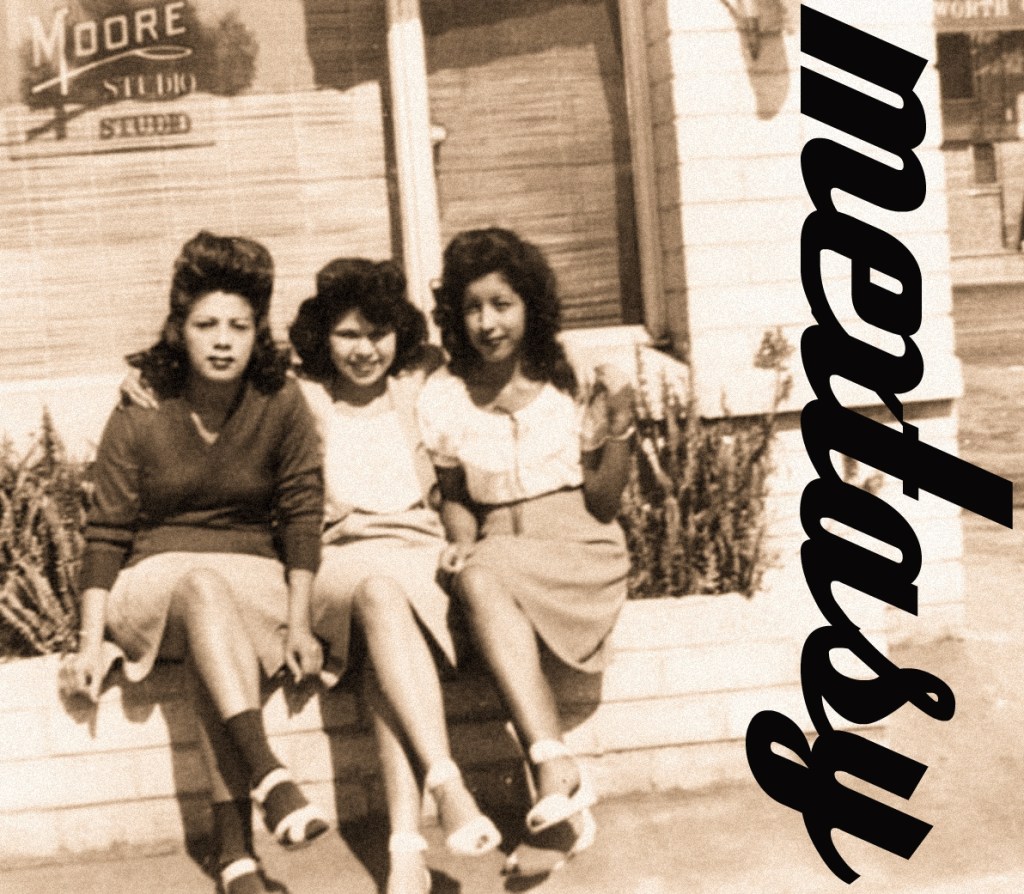

Nina Vera sits atop the cool old car, hand to hair, addressing the camera with the knowing look of someone going somewhere. Many of the pictures on this site give voice to strong women, rucas and veteranas of substance, whose beauty is a function of their strength, their strength somehow locked dialectically with their beauty. Are we speaking of an aesthetics of power or the power of aesthetics? It does not matter. All that echoes back to me is the pathos of the photograph, a relic of a woman and a moment fading past memory.

As moving as the photographs are the commentaries of those who remember, those who reach out, sharp arch missives from friends from the past immortalized (or, as immortalized as you can get on the internet) by the archiving power of a hashtag, of a website. Instagrams, like the Western Union Telegrams from the past that inspired their name, hit with the power of life and death, a snapshot from yesterday that reaches out from the past to the future with the power to compel you to return, to memory, to pieces of yourself you left behind, hid, or forgot.

I am the youngest of three children born and raised in Laredo, Texas, with two older sisters, so perhaps I am drawn more to the photos of women—my memory of being a young man in Laredo is always bound up with my outsider status, too gringo-affiliated (Gilligan’s Island more my cup of tea than Siempre en Domingo) and too pocho to be truly Laredense, I was never just one of the vatos.

Similar complications and my own teenage awkwardness led to a similar status with the ladies, but still, old habits die hard. So I find myself witnessing the images of these rucas, watchful of the evolving styles of hair and dress of the veteranas, time and again.

Do you look at pictures as I do? I look into the faces and wonder about the secret yearnings of their hearts—their frustrations, their ciphered dreams and desires. Looking closely, I try to piece together answers to the mysteries of strangers with whom I have no history, no knowledge, looking for some kind of magic Rosetta stone that will translate their muted testimony into something I can understand.

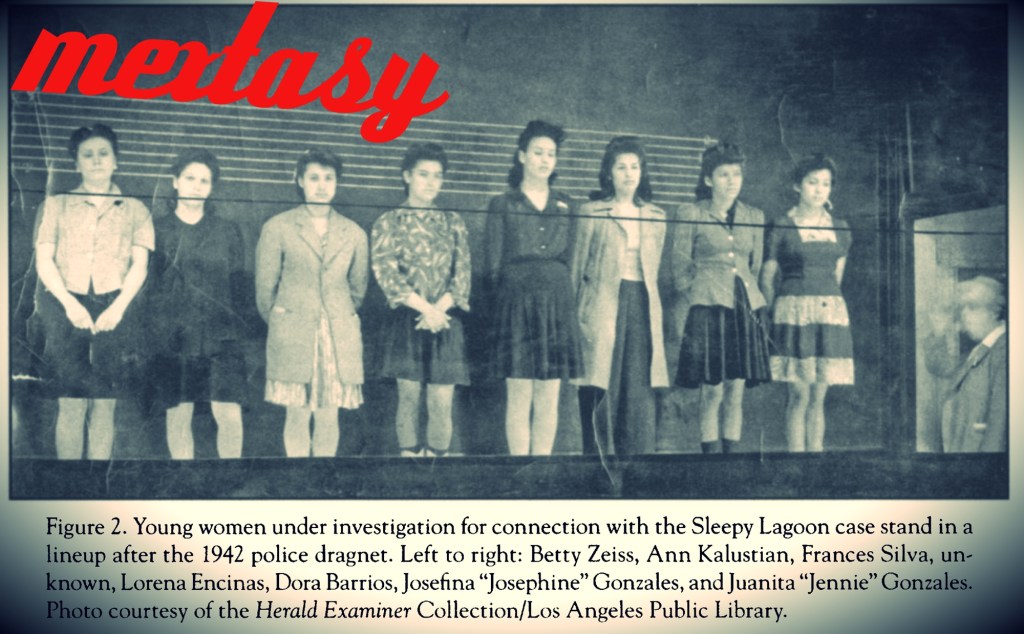

In my art, I try to give honor to women of these lost generations—to evoke the mextasy of a yesterday that should be part of today. Here are a couple:

I will end here with a picture of some vatos, rucas, veteranas, and more from my own past—it is 1981 and a group of old friends from Laredo, Texas, are drinking it up at a friend’s apartment in Austin, Texas. See if you can pick me and my girlfriend Rosalinda Flores out, we are the ones smiling back at you on the right.

This article is a reproduction of the original blog post by William A. Nericcio in Duke University’s academic program, Latinos in the Global South. POCHO copied it from LatinoLiteratures.org. It is reproduced with permission from the author.

- William Nericcio is the author of numerous peer-reviewed articles in journals including Camera Obscura, Americas Review, Spring, the Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies, and Mosaic. In 2007, The University of Texas Press published his American Library Association award-winning cultural studies volume Tex[t]-Mex: Seductive Hallucinations of the “Mexican” in America. His next book, Eyegiene: Permutations of Subjectivity in the Televisual Age of Sex and Race is presently in development. He is also the author of two edited collections (Homer from Salinas: John Steinbeck’s Enduring Voice for California and The Hurt Business: Oliver Mayer’s Early Works [+] PLUS) for San Diego State University Press. Most recently, he assisted philosopher Mark Richard Wheeler with his critical anthology, 150 Years of Evolution: Darwin’s Impact on Contemporary Thought and Culture for SDSU Press and helped edit and design Secession, with Amy Sara Carroll, with Hyperbole Books.

- More POCHISMO from Memo Nericcio is here