I approach el Cinco de Mayo with excitement and ambivalence.

I approach el Cinco de Mayo with excitement and ambivalence.

I learned the history of the Battle of Puebla as the son of proud Mexicans, who happened to be immigrants. The story goes: On the fifth of May 1862, a small Mexican army kicks French butt. Bueno.

My dad and grandmother worked at the Cinco de Mayo restaurant on Pacific Coast Highway in a small L.A. harbor town. My association with the day is food, drink, familia, history, cultura.

Now, it’s Drinko de Mayo at a bar near you, the

¡FIESTA AT FIG!, Eastside Luv’s thang, or the Cincléctico concert at the Regent Theater in DTLA. Check out our Calendario for more.

But the traditional hasn’t disappeared – there are places in L.A. that feature the speeches, reverence and pride; traditional food, music and dancing. The Mexican state of Puebla, where the battle took place, represents with in L.A. with art shows, receptions, fiestas and a celebration at Olvera Street with live streaming on big screens, on both sides of the border. You can even watch the movie: Cinco de Mayo: La Batalla.

My stance evolves: Right now I am still reeling from the realization that Cinco de Mayo may not have originated in Mexico, after all. Yes, the battle took place that day, but when and where did the party really start?

My stance evolves: Right now I am still reeling from the realization that Cinco de Mayo may not have originated in Mexico, after all. Yes, the battle took place that day, but when and where did the party really start?

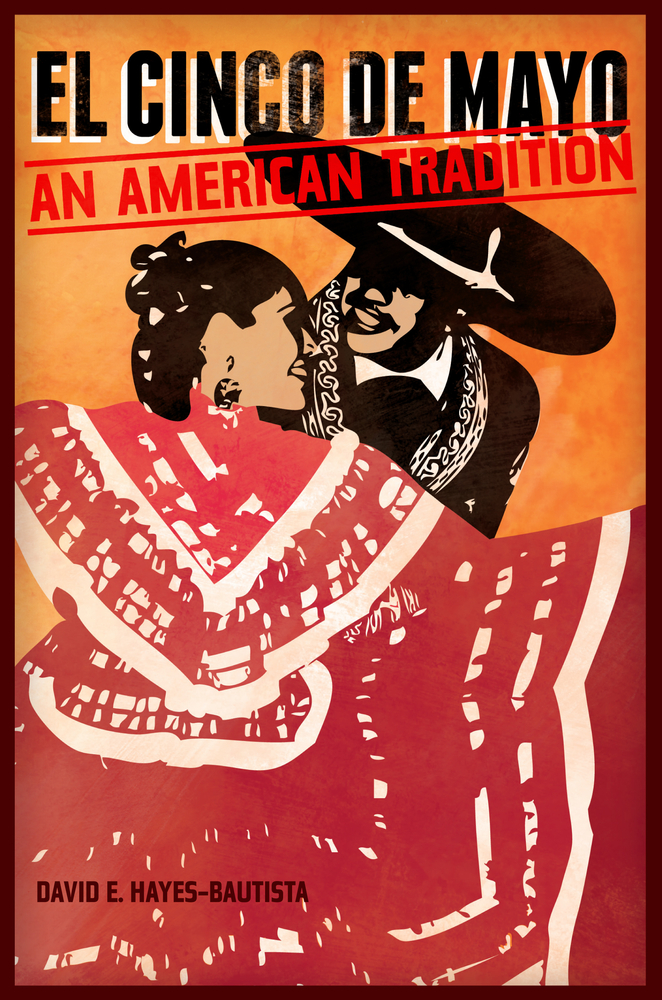

UCLA’s David Hayes-Bautista of the Center for the Study of Latino Health and Culture, author of Cinco de Mayo: An American Tradition tells the story this way:

Cinco de Mayo became a rallying cry for Mexicans living in the United States during the American Civil War. Mexico, the first country to abolish slavery and racial discrimination, was also in a war to keep its freedom.

Mexicans in the Union Army supported the Mexicans with cash, support and shared values. Mexican win the battle, lose the war, fight some more, win the war. Since then, in Mexico, Cinco has been celebrated with a small military parade; Here in the U.S., bolstered by the Union victory, the Mexicans kept the parties and they’ve only gotten bigger.

Dr. Bautista’s got a busy weekend.

I’ll go over to Olvera Street, L.A.’s traditional Mexican gathering place, to listen to music and be close to mi gente.

Will I hear mention of Benito Juarez, Mexico’s president during its war with France? Or of General Zaragoza, leading an army of Mestizos and Zapotecs. Or of Maximilian, sent by French emperor to settle on debt by taking over a country?

Doubtful. But just because that’s my cultural memory, it doesn’t have to be anybody else’s. I accept Cinco’s commercialization as a day / weekend of celebration. I’ll drink a Dos Equis sometime, I’m sure. I’ll shout out a ‘grito’ if I hear a mariachi, dance to a ranchera or some Latino EDM. And I’ll remember the large painting at the Cinco de Mayo in Wilmington – fighting and falling men, cannons, horses,flags, smoke and blood.

C’mon, have a tequila!

At its core: Mexicans fought and won, OK, let’s party.

I draw my line, however, at Lime-A-Rita and Straw-Ber-Rita.